“If you’re not sure what to do, just ask.”

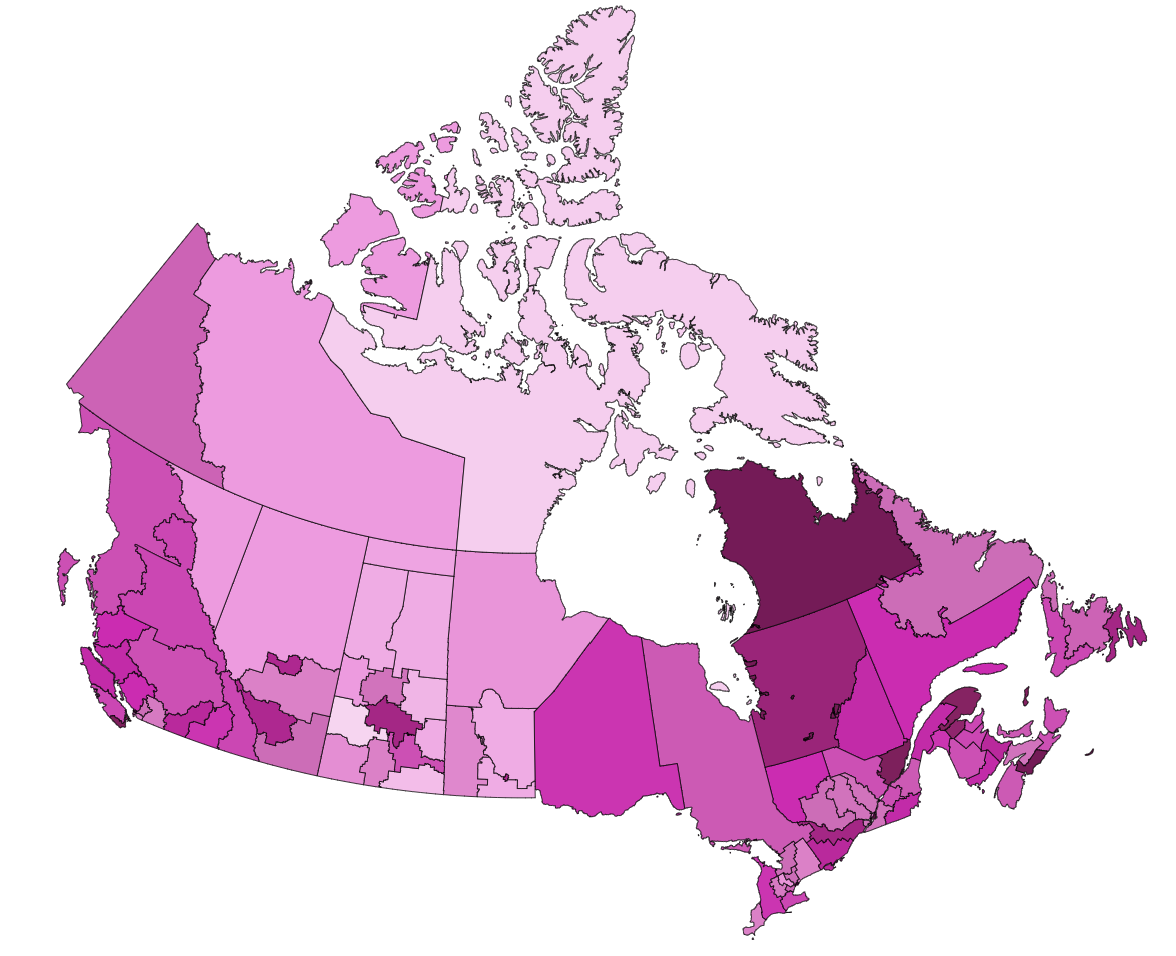

By David Berman, with Maham Farooq and other contributors at David Berman Communications

[Thank you also to the Canadian Association of the Deaf, and CAST for their help! Some content used with permission from Brian Kon and from the Disabilities Issues Office, Government of Manitoba.]

If you don’t have experience hanging out with people with disabilities, you may fear doing or saying the “wrong thing”, especially when you’re at a meeting with people you’ve just met.

Interacting with everyone can be pretty easy. People living with disabilities are people first: needing mostly the same things that every person needs. The best plan is to show respect by focusing on the person, not the disability.

You can think of distance participation as a basket of temporary disabilities: not being able to see or be seen, hear or be heard, or otherwise interact in ways that are easy to do in person and when fully abled.

So let’s get you comfortable and poised to help everyone get the most from every meeting……

Welcoming everyone

Treat everyone with respect. If you are unsure what to do or how to assist someone, ask them. A person with a disability in an unfamiliar environment may be much more vulnerable or awkward than in familiar surroundings.

It’s very cool that you’d like to help: however, do ask first … what you think might be helping may be the opposite.

Just because someone is blind does not mean that they are Deaf. And just because they are Deaf doesn’t mean they are blind. If you’re not sure what to do, just ask: treat others the way you would want to be treated and we’ll all be okay!

So first, get comfortable with what words are best…

Vocabulary

- In general, refrain from using negative terminology to refer to differing abilities. For example, a person is not confined to their wheelchair, they use a wheelchair.

- Avoid terms such as disabled or handicapped; however, the word “disability” is acceptable and “living with a disability” can be even nicer.

- Use people-first terminology (except with people from Deaf or Autistic cultures). For example:

- “Dr. Durocher is a person living with a disability.” instead of “Dr. Durocher is disabled.”

- “Joe Singh uses a wheelchair.” instead of “Joe Singh is confined to her wheelchair.”

- “They are a person with quadriplegia.” instead of “They are a quadriplegic.”

- …but “Jak Johnson is Deaf” instead of “Jak Johnson has a hearing disability” and “Ahmed is hard of hearing” instead of “Ahmed is hearing-impaired.” (because the Deaf community doesn’t consider not hearing to be a disability nor an impairment).

- Use respectful terms when referencing persons living with disabilities:

- “people” or “all of us” instead of “those people”, “you people”, “them”

- “person living with a disability” instead of “the disabled”, “the handicapped”, “special”, “deformed”

- “person living with mental illness” instead of “person with mental health issues” or “mentally ill”, “insane”, “crazy”

- “person with a mobility disability” or “person with a _____ injury” instead of “physically challenged”, “crippled”, “lame”

- “person who uses a wheelchair” instead of “person confined to a wheelchair”

- “person who has diabetes”, “person living with arthritis” instead of “diabetic person” or “person suffering from arthritis”

- “accessible parking/washrooms” instead of “handicapped/disabled parking/washrooms”

- “person without a disability” or “typical people” instead of “normal”

- …and, please, let’s all just stop using the words “dumb” and “dummy” as a synonym for stupidity!

- Warning: You may, understandably, be tempted to use terms based on the names of organizations or documents with historical names. Don’t. For example, don’t refer to people of atypical abilities as “disabled” because you see the word “Disabilities” in the Americans With Disabilities Act (1990). This would be like referring to indigenous people as “Indians” inspired by the Indian Act (1876) or talking about “colored people” based on the spelled-out version of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People).

Blind and low vision

- Instead of “blind person” or “the Blind”, say “person with visual challenges” or “people who are blind”.

- Most of these tips are appropriate for both people with low vision as well as those who are blind.

- Many people who are “legally blind” have some sight: A person can have significant vision loss to the point they are considered legally blind, but that does not mean they cannot see. For example, some conditions create black areas in the middle of the person’s vision allowing them only to see in the periphery of their field of view. Other conditions create dark outer edges as if they are looking through a tunnel while maintaining 20/20 vision in the middle. Some people view the world through a haze; others can only see light versus dark. It is important to note that a person who uses a white cane, or has a service animal, may be able to see well enough to move about their environment. They may also be able to see facial expressions yet can’t read text.

- It can be difficult to differentiate between a person being blind and a person living with low vision: Your best clue to how much vision the person has is likely by observing how they move within the environment.

- When identifying with the disability community, the choice of identifying as a person who is blind versus as a person with low vision is a personal one.

- Phrases like “see you later” and “read this” when interacting with someone who can’t see are fine and natural.

- The blind community is fine with you calling blindness a “disability”

- The proper noun “braille” is not capitalized (even though it’s named after Mr. Braille!). Braille is an alphabet (or “code”), not a language.

Deaf and Hard of Hearing

- The Deaf community:

- uses “Deaf” as a capitalized word, so you should too

- distinguishes between “culturally Deaf” (for someone born deaf and typically exposed to Deaf culture) versus someone who, due to profound hearing loss later in life to the extent that they are medically considered deaf, is native to a hearing world.

- does not classify being Deaf as a disability (except in certain regulatory situations) … and thus prefers “identity-first” language rather than “person-first” language

- has sign languages as their native languages

- ASL (American Sign Language is the main sign language used in the USA and English Canada), LSQ (Langue des signes québécoise) in French Canada.

- Other popular sign languages in North America include LSM (Lengua de señas Mexicana), Plains Sign Language (PISL), IUR (Inuit Sign Language – Inuktitut: Uukturausingit ᐆᒃᑐᕋᐅᓯᖏᑦ or Atgangmuurngniq ᐊᑦᒐᖕᒨᕐᖕᓂᖅ) in northern Canada, and a variety of other indigenous and regional sign languages.

- Sign languages are not a format nor a dialect of spoken languages: they are distinct languages, each with its own grammar and syntax.

- Just like written languages, sign languages have local accents and colloquialisms based on where you live: the Canadian dialect of ASL is as different from American ASL as Parisian French is to Quebec French or Castilian Spanish is to Colombian Spanish.

- People who grew up hearing and then lost hearing later in life (“Hard of Hearing”, “Deafened”) typically prefer captioning and are more than likely not fluent in a sign language

- Acronyms you may come across:

- “DHH”: Deaf people and people who are Hard of Hearing

- “HoH”: people who are Hard of Hearing

- “DDBHH”: Deaf people, Deaf-Blind people, and people who are Hard of Hearing

Neurodisabilities and intellectual differences

- The Autistic community includes many who prefer “identity-first” language rather than “person-first” language. That means you’d say “Autistic” rather than a person “living with autism”.

- Use respectful terms when referencing what people can do: say “high support needs” and “low support needs” rather than “high functioning” and “low functioning”. Even better, refer more specifically to their cognitive or verbal abilities.

- Use “on the spectrum” or “autism spectrum condition” rather than “autism spectrum disorder” or “disease” or “illness”.

- Use “intellectual difference” or “intellectual disability or “neurological developmental disability” rather than “mentally handicapped”, “learning disabled”, “developmentally delayed”, “mentally retarded”, or “mentally challenged”

- When comparing to typical people, use “neurotypical” and “typical adults” and “typical developing children” rather than “normal” or normally developing” or “healthy”.

Introductions

- Give people who are differently-abled the option to self-identify during introductions and/or in their “screen name”.

- Be patient: Remember to give everyone the time and space they may need in order to feel comfortable, possibly needing more time than you are accustomed to for settling in and interacting.

“People with disabilities are individuals with families, jobs, hobbies, likes and dislikes, and problems and joys. While the disability is an integral part of who they are, it alone does not define them. Don’t make them into disability heroes or victims. Treat them as individuals.” – United Spinal Association

Interacting with everyone

In general, if you’re not sure what to do, just ask. And if you’re not sure exactly what to say, try this: “Would you like any help?” …beyond that, how to interact best depends on the individual.

Person accompanied by an attendant or interpreter

- When meeting or greeting any person with atypical abilities, consider our general advice above about welcoming everyone.

- Attendants or interpreters may be paid professionals, friends, or family members. Interpreters may be interpreting between two spoken languages, between a spoken language and a sign language, or even between two sign languages.

- If an attendant or interpreter accompanies the participant, you could ask the participant if their attendant will be present throughout the event. When the attendant or interpreter is present, direct any exchange to the participant, not their attendant. While it may seem strange to you, an interpreter is not a “participant” per se when you are interacting with a person with a disability.

- If an interpreter is introduced to you or to the group at all it will typically only be to state their role. While in the role of interpreter, they should not be involved in the discussion other than to faithfully share messages amongst participants. In their role as an interpreter, they will typically share everything you express: that’s their job.

- Participants needing to see sign language interpretation will want to “Pin” the interpreter so that they can see their full video, larger, and in the best place for them on their screen.

- Participants needing spoken language interpretation will either rely on captions or a separate voice channel using technology outside of what is possible on the meeting platform.

Person with a motor, mobility, or dexterity challenge

- When meeting or greeting any person with atypical abilities, consider our general advice above about welcoming everyone.

- Be patient: If a person can’t use a mouse, they are likely to navigate the online space in a way that is slower or more awkward than for participants using a pointing device. For example, they may be using a foot pedal to step through every selection in the interface before getting to select the one they need. If there is an anticipated wait before an event begins or before moving to a breakout room, you can offer the person help to find their place.

- Be ready to be helpful: Proudly know the shortcut keys for anyone who is struggling to get stuff done at game speed.

Person who is blind or has low vision

- When meeting or greeting, consider our general advice above about welcoming everyone as well as our vocabulary for blind and low vision.

- Bias towards being the first person to speak in an interaction with someone who is blind or has low vision, as you will likely have more context than they will.

- Blind or low vision users will typically use a combination of assistive technologies to help them interact without relying on vision:

- Screen readers can announce everything that is relevant on the screen as the user navigates to each element (typically tabbing through each element, as using a pointing device is not feasible for someone who can’t see where the pointing device is located). The screen reader also may announce what they type (typically wired to their headset for both privacy and to avoid distracting others). Because the user is also potentially trying to listen to you express yourself, don’t be surprised that there may be long pauses while the participant switches between listening to you; listens to what’s in the chat, listens to the interface; listens to what they are composing in the chat; etc. Don’t be surprised to occasionally hear the screen reader chatter in the background: it may be at a speed so fast you won’t be able to understand it!

- Dynamic braille displays present information in braille, and are often used by those fluent in braille in concert with a screen reader (this is especially helpful when someone has the screen reader announcing what they type)

- Magnifiers enlarge what’s on the display and may limit what can be seen at once or cause interface objects to overlap.

- Be aware that the experience of someone who has never seen is substantially different from that of someone who had typical vision at one point but doesn’t have it now, or may still have some sight. For example, someone who recalls what things look like may rely on those memories or use visual concepts to organize information very differently than someone who has always relied upon audio or tactile approaches. They could, for example, be able to sign a physical document, with limited assistance or understand a context that is instructing others based on color. If you don’t know, assume they have never seen: if you feel comfortable, the first time it would help you help them to know, you could privately ask them for permission to ask (including telling them why you are asking).

- If you are in a physical space and have the opportunity to assist the person when moving to a new location, you would first ask if you could assist. If they do want help, you would position yourself on the side of the individual opposite to their white cane or service animal. You would then extend your bent arm back so that your elbow touches their upper arm. They would grab onto your upper arm (don’t grab them!) and then hold on to you as they follow slightly behind as you walk. … and the same applies online: offer to help them get where they want to be.

- Guide dogs (like all service animals and other accommodation tools and assists) are personal: don’t interact or touch them unless invited to. Don’t take it personally if you’re told not to!

- If you were in a physical space, and your path of travel changes in elevation (such as stairs) or moves through narrow spaces (doors, narrowed hallways), you would let them know what is happening. When going through doorways, you would maintain your position slightly in front and tell them you are about to go through the door; then extend your arm back so the two of you take up less width to fit through the door. The equivalent in an online meeting, if the platform has such a feature.

- When leading a person to a place to sit, you would identify where the chair is in relation to where they are now, and describe a brief layout of the entire space

- Whether in a physical or a virtual space, you want to ensure that a person who cannot see is aware of who else is present. Also, tell them about anything else that is unexpected: for example, in a physical space, you’d warn a non-visual person that you’ve put a cup of coffee in front of them (perhaps based on clock directions): in the virtual space, you may wish to mention that the presenter was wearing a badger costume but now has wandered off camera.

- If you are in an audience for a live presentation that may include people without typical vision, the presenters should be either live-describing anything relevant that can only be seen (for example, a picture on a slide being shown) or providing an audio description of some sort. This way those who cannot see are still aware of all relevant content. Similarly, if you are expressing yourself in a meeting and referencing anything visual (for example, you are holding up a puppet of a badger), you need to also gain the habit of live-describing what is relevant (for example, “It’s a puppet of a badger… not an actual badger!”) … unless there is a formal audio description service in the meeting, in which case you can also rely on that audio track).

- A great habit is to self-identify the first time you begin to express yourself and every time at least two other people have spoken since you last spoke (e.g., “David Berman speaking”). This helps everyone, including interpreters and transcribers, know who’s speaking, as well as gives people a moment to remember who you are. It may seem awkward to you at first… you’ll get used to it, and everyone will appreciate it immediately and learn from your example.

- When directing a question at someone, state their name: don’t assume that visual or conversational cues will be obvious to them (as well as to others who may think the question is directed at them!).

- The environment can have a big impact on a person with low vision’s ability to use what residual vision they have. For example, if you are visible, be in a well-lit space that is not so bright that it would be hard on someone who has light sensitivity (avoid having an outdoor window behind you).

- Just like in a physical space, if someone enters or leaves the space, we want everyone to know.

Person with a color deficit

- When meeting or greeting any person with atypical abilities, consider our general advice above about welcoming everyone.

- Whether someone has a complete color deficit (which is quite rare) or doesn’t see all color typically, be careful not to provide instructions or presentations that rely upon color alone to succeed. For example, say “Meet me in Room 1 (the blue one), rather than “Meet me in the blue room”.

Person who is Deaf

- When meeting or greeting, consider our general advice above about welcoming everyone as well as our vocabulary for Deaf and Hard of Hearing (especially concerning “Deaf” and “disability”).

- A Deaf person may not have the ability to speak in a typical way. Therefore, they may use a different form of communication. In a physical space, for example, they could present a pre-printed card self-identifying that they are Deaf. In the online space, they may add “(Deaf)” to their meeting name (just like someone may self-identify their pronouns as “(he/his)”).

- A Deaf person may have some hearing. Often they are able to use devices such as hearing aids (which amplify sounds) or a device known as a cochlear implant (a device that simulates sound by sending electrical impulses to the auditory nerve which the person interprets as sound or words).

- If a Deaf person also knows, for example, English (often referred to as being “bilingual” in the USA), take into account that it is their second language (just like anyone in an “ESL”-like situation) and therefore may not be as strong as that of other participants when expressing themselves in another language. They may struggle to fully understand your written messages, and their own written messages may not be well-expressed or in the expected word order (due to the grammatical differences between their native sign language and the spoken language).

- If you don’t know how to sign (or don’t have a signed language in common with the person), consider learning sign language (even some basics): it’s fun and will unlock your creativity in ways you don’t expect!

- If a sign language interpreter is present, always speak directly to the Deaf person (ignore the interpreter… it’s their preference too: you won’t offend them!). The interpreter will announce the person’s response if they cannot speak.

- If there is no sign language interpreter nor captions (and your signing ability is not sufficient for the topic), use written forms (live chat, hold up a written message in view (using pen, paper, tablet,…) or AI live transcription if it will be of sufficient quality.

- Take full advantage of how virtual spaces help Deaf people (compared to a virtual space where everyone is, for example, around a table) because they can line up everyone visually side-by-side rather than having to search the room guessing who may start speaking or signing next (and often missing content because of it).

- Depending upon their fluency in the language of the captions, quality of the captions, and personal preferences, Deaf people may take advantage of captions … especially if sign language interpretation is not available.

- Be patient, because interpretation or captions (especially quality captions scribed by a human interpreter) are often delayed five seconds or more.

- A Deaf person may be augmenting limited hearing by watching your lips or facial expressions. Therefore, definitely be on camera in a virtual meeting. Also, avoid hiding your face (for example, behind a coffee cup) or look away while speaking, as portions of the conversation may be lost. Similarly, if the other person is looking away, for example, while needing to view a document, wait until they look at you again before speaking.

- To get the attention of a person who cannot hear in a physical space, it would be appropriate to wave within their field of vision, gently grab their upper arm, or knock on the table. In a virtual meeting, you do the same. The “Raise hand” feature in the meeting’s software is not a good substitute because it is not directed at an individual. Deaf people will often use this same technique to get the attention of anyone in the meeting, including signaling to the interpreter that they wish to contribute.

- Make sure you are in a well-lit space so that your lips and facial expressions are easy to see: this will help these assistive characteristics be easily available to all who wish to follow the conversation. Avoid having an outdoor window or a source of bright light behind you. (PS All sighted people lipread: you may not even notice that you do it!)

- If you need an unobscured view of the sign language interpreter, consider arranging your view so that, for example, notification windows or dialogs won’t get in your way.

- DeafBlind people will typically have a specialist interpreter, fluent in tactile sign language, as well as specialized assistive technology.

Person who is hard of hearing or deafened (or processes spoken language atypically)

- When meeting or greeting, consider our general advice above about welcoming everyone and our vocabulary for Deaf and Hard of Hearing.

- A person who is hard of hearing or deafened will often have some residual hearing. Often they are able to use devices such as hearing aids (which amplify sounds).

- A person who is hard of hearing or deafened will very possibly be able to speak.

- It may become obvious that a person is not paying attention to instructions, or is having difficulty hearing the conversation. If so, make eye contact with the person when presenting. As well, if they are not looking at you (for example, they may be recording information), wait until you have their attention.

- Eliminate background noise at your end: turn off background music or televisions, close your door, turn on noise suppression, and ask others in your area to lower their noise level. And mute your mic when not speaking.

- Try adjusting the position or volume of your microphone … consider a better microphone: avoid using the built-in one on a laptop or smartphone.

- It may be necessary to speak with more volume, but do not shout (shouting distorts the sound, making you more difficult to understand).

- Speak in a natural voice: do not exaggerate the words when you speak.

- If it is clear the person is having difficulty hearing your message, try using different words to say the same thing.

- Keep in mind that many of these points are also relevant in a situation where you are accommodating someone whose native spoken language is different from yours.

- Take full advantage of how virtual spaces help people who are hard of hearing (compared to a virtual space where everyone is, for example, around a table) because they can line up everyone visually side-by-side rather than having to search the room guessing who may start speaking or signing next (and often missing content because of it).

- Unless the captions are poor, people who are hard of hearing will rely heavily upon them: be patient, because the captions, especially quality captions written by a human interpreter, are often delayed five seconds or more.

- They may be augmenting limited hearing by watching your lips or facial expressions. Therefore, definitely be on camera in a virtual meeting. Also, try not to hide your face (for example, behind a coffee cup) or look away while speaking, as portions of the conversation may be lost. Similarly, if the other person is looking away, for example, while needing to view a document, wait until they look at you again before speaking.

- Make sure you are in a well-lit space so that your lips and facial expressions are easy to see: this will help these assistive characteristics be easily available to all who wish to follow the conversation. Avoid having an outdoor window or a source of bright light behind you. (PS Everyone who is visual lipreads: you may not even notice that you do it!)

Person who is unable to speak or has challenged speech (or challenged signing)

- When meeting or greeting, consider our general advice above about welcoming everyone.

- Challenged speech can be due to a variety of situations, including aphasia, delayed speech, no speech capability, articulation challenges, or a lack of knowledge in a particular language.

- Don’t assume that just because someone has challenged speech that they don’t hear and comprehend typically.

- If a person stutters or needs more time, do not finish their thoughts. Wait patiently for them to finish before responding.

- Do not assume you have understood the meaning of what they are saying before they are finished.

- If you have difficulty understanding what a person is expressing, ask them to repeat, rather than trying to guess what was said. If, after a second try, the message is still unclear, ask them to try telling you again using different terms.

- Captioning technology (and human captioners) can be quite challenged by atypical speech.

- Some people with challenged speech or no speech will use sign language to express themselves, and thus may benefit from the presence of a sign language interpreter. Others may rely on the Chat feature (or similar technologies).

Person using a speech synthesizer or other expression assists

- When meeting or greeting, consider our general advice above about welcoming everyone.

- A person using a speech synthesizer (e.g. some Deaf people or people with challenged speech or no vocal ability) will type their message into a device that announces the message for them. In some cases, they will have set the machine to spell out each letter back to them audibly as they compose. Once they have completed their full thought, they will cause the machine to announce it, in a voice that may sound robotic or mechanical. While the person is entering the message don’t talk or sign to them: let them complete their thought.

- Speech synthesizers include tablets, computers, smartphones, and specialty portable electronic devices.

- Be aware that the synthesized voice may not always match the voice you are familiar with or expect for that person.

- Some people use portable communication boards (digital or physical) that simply include letters of the alphabet and other symbols to point at. As they point to a symbol, state the letter or idea they are pointing to – this helps them know that you are following their conversation. When you get to the end of the word they will pause, this is your cue to state the word: they will confirm and then move on. This form of communication uses the least amount of words to get the message across.

Person with an intellectual, neurological developmental, or learning difference

There are a wide range of conditions that may present differently for a person with an intellectual or neurologic difference. Examples include Tourette’s syndrome (or other conditions on the autism spectrum), dyslexia, ADHD, dysgraphia, mysophobia, or memory or distraction challenges. These affect how the person’s brain interprets information and how they respond to the information or their environment. It is not a reflection of their intellect. These may be difficult to determine unless the person identifies they have a disability or difference.

- When meeting or greeting, consider our general advice above about welcoming everyone and about neurodisabilities and intellectual differences.

- In a physical space, the room could be set up to minimize distractions from the conversation by positioning people so they are not looking out a window or open door, and reducing background music or voices. Online we can do the same by attending to our camera backgrounds and any background audio.

- Reading challenges: People with an attention deficit or a reading disorder may read materials multiple times before they can absorb the content. A person who has dyslexia may struggle to process written language (which can impact their fluency, comprehension, and decoding). Therefore, they may ask to take the material home to read. If there are lengthy documents that need to be read, provide a few private minutes and allow the person to concentrate on the material without being distracted: reading can be more challenging if they are being “watched”.

- Some people are challenged with orienting items spatially or sequentially. This may challenge how you provide step-by-step instructions. The challenge is often in the translation of the instructions into the “real” world.

- During any timed activities, consider that the person may focus more on the clock than the activity.

- Similar to dyslexia is a condition called dyscalculia, which causes a person to struggle with numbers instead of letters: they may need time to use their calculator for simple arithmetic.

- A person with a neurologic disorder may handle stressful situations with vocal or facial tics (which may lessen as they become more comfortable with others present).

- A person may be managing a disorder with medication: the medication’s dosing schedule may dictate that they simply can’t be attentive, sharpest, or even present, on specific days or specific times of day.

Did you know?

In the Cree language, autism is not considered a disorder.

Their word, pîtoteyihtam, instead means “they/he/she thinks differently”.

In general

- Be patient:

- Anticipate that it may take longer for someone to react to you in a meeting should they have a mobility or vision challenge because it can simply take longer for them to locate and action the interface commands without the benefit of a mouse or other pointing device.

- Similarly, if someone is using some form of interpretation, it will take longer for them to receive your message or for their response to be available to you

- Choose clothing and backgrounds that sharply contrast with your skin colour, so that everyone can pick up your face and body language more easily … especially those who may be lip reading or interpreting your sign language. Dark (such as black or navy blue) works best if your skin is lighter; light hues (such as white or yellow) work best if your skin is darker. Also avoid plaids, patterns, and complex designs. Green can be especially problematic, as it often cannot be picked up by people with a vision deficit.

- Choose backgrounds with little or no motion (including poorly-performing virtual backdrops that distractingly cause objects or body parts to appear and disappear), since they can affect people who have attention deficit disorder, motion sickness, dyslexia, epilepsy, or migraines, as well as those trying to follow sign language presentation.

- If the other person is having difficulty hearing or understanding you:

- Use different words that have the same meaning (For example: change “How may I help you?” to “What can I do for you today?”)

- Be aware of how quickly you speak. Say each word individually (while keeping a natural flow, so you don’t sound condescending to the other party).

- Ask the person if they know whether they are in a quiet area or whether they can move to a quieter area – it may be their background noise that is interfering with their ability to hear.

- It is also possible, either as a last resort in the absence of captions or interpreters in the meeting that a Deaf person, Deaf-blind person, or person who is hard of hearing or unable to speak could choose to use a “relay service” where a human interpreter interprets or voices a typed conversation they are having on a different platform with that person (or a “video relay service” where a sign language interpreter phones into the meeting, is the voice of the Deaf person who has joined the meeting in the normal way, and backchannels with the Deaf person using separate video software).

- Remember that, just like with so many personal preferences, some people are proud and eager to share their differences (as well as their experiences of it), while others prefer privacy.

- In general, feel free to offer people help, especially if it’s their first time on the platform… “May I help you?” is always appreciated, and then let them decide if they’d prefer to get whatever done independently!

You’ve got this!

There are many types of disabilities. Circumstances can cause anyone to have a temporary disability if they are without their assistive technology. For example, a person wearing glasses has no trouble driving to work, but if those glasses are lost or broken, are they capable of driving home?

Or perhaps someone who typically wears glasses has them off due to temporary fogging from their COVID mask. And everyone, especially those who lipread or depend on facial cues, misses out when watching someone wearing a mask (stylish!)

Governments have a wide definition of disability. Rather than focus on names or types of disabilities, deal with the person – in other words, interact with the person based on what they are experiencing, not the diagnosis. For example, while it can be contentious whether obesity should be considered a disability, the fact is that a person who is obese may have difficulty walking, or they may be short of breath, or they may be less agile and have difficulty bending their body and may need accommodation. In the same way, a woman in her third trimester of pregnancy is not a person with a disability, but she too may have difficulty walking up a flight of stairs. And simply not being fluent in the primary language of the meeting (even to the extent of bringing a language or cultural interpreter) is an imposed disability too. Accommodation varies by person, circumstance, and the environment they are in.

If you are unsure of what to do, the best approach is simply to ask the person how you can help!

Go deeper

For deeper tips on accessible events, visit davidberman.com/accessible-event-tips or consider David’s learning guides and courses. Do you have tips to add? Tweet me @davidberman.

David Berman’s team has extensive experience, on five continents, in helping to publicize and run meetings and conferences. We can help your meeting plan team to create events that include everyone, from the first email campaign through to the final evaluation. Our services include accessible communications (we have a full-service mainstream graphic design team at your service), email, social media, site planning, document remediation, website and built environment auditing (and programming), accommodation services (e.g., sign language interpretation, CART captioning, large print editions, review of speaker support files), accessible AV services, and evaluation. As well, we can train your team and presenters on general sensitivity, introductory sign language, and accessible document development.

David Berman, CPWA, ADS, RGD, is a special advisor to the United Nations on how to use accessible design to fulfill the Millennium Development Goals. His book Do Good Design is available in English, Chinese, Indonesian, Korean, Malay, Russian, Spanish, and braille. http://www.wcag2.com